When the Body Was Divine

Installment B of the Essay Series

There was a time when the nude body wasn’t scandalous.

It wasn’t blurred, flagged, or covered in fig leaves.

It was divine.

Across ancient cultures, the exposed human form was revered. Nudity wasn’t an invitation to look away—it was an invitation to look deeper. Statues stood naked in temples. Lovers and deities adorned the walls of shrines. And no one called it pornographic.

In early Mesopotamia and Egypt, gods and kings were sculpted with idealized bodies—torsos bared, phalluses proud, hips soft and strong. These weren’t airbrushed fantasies. They were sacred representations of power and presence. In Greece, athletes competed nude, and philosophers debated beauty like it was a spiritual principle. The naked form was considered closer to the truth.

In Hindu and Buddhist traditions, erotic carvings weren’t tucked in back corners of temples—they were carved right into the front doors. Visitors entered through imagery that we, today, would likely tag as explicit. But there, these figures were teachings. Desire wasn’t a detour on the spiritual path—it was part of it.

The same goes for ancient fertility icons—like the Venus of Willendorf or thecSheela-na-gig—figures with generous thighs, exposed genitals, and wide, unapologetic eyes. In their time, they were symbols of life and abundance. Today, they’d likely be pixelated—or banned altogether.

Venus of Willendorf

Sheela-na-gig

So what happened?

As Christianity took root—especially in the West—the body lost its sanctity. Slowly, reverence gave way to restriction. Nudity became dangerous. Pleasure became suspect. The naked body? A liability. A threat. A thing to cover.

The early Church didn’t just rewrite theology. It reshaped how people viewed their own bodies. A naked figure once considered sacred became something to hide. Something to judge. Something to feel guilty about.

By the Middle Ages, robes and loincloths had been painted across religious art. Nudity still appeared, but now it needed a narrative: suffering, shame, sin. Even during the Renaissance, with its revival of classical ideals, tension remained. Michelangelo’s Last Judgment originally featured a sea of unapologetic nudes. After his death, the Church ordered the genitals covered. The man hired for the job, Daniele da Volterra, became known as Il Braghettone—“The Breeches Maker.”

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment

Centuries later, Pope John Paul II would call for the restoration of many of those same nudes. He emphasized the importance of distinguishing between the ethos of the image—the artist’s intention—and the ethos of the viewer—what the audience brings to it. A rare moment of official reclamation. But by then, shame had already rooted itself in the folds of fabric, in the downward gaze, in the reflex to look away before desire gives us away.

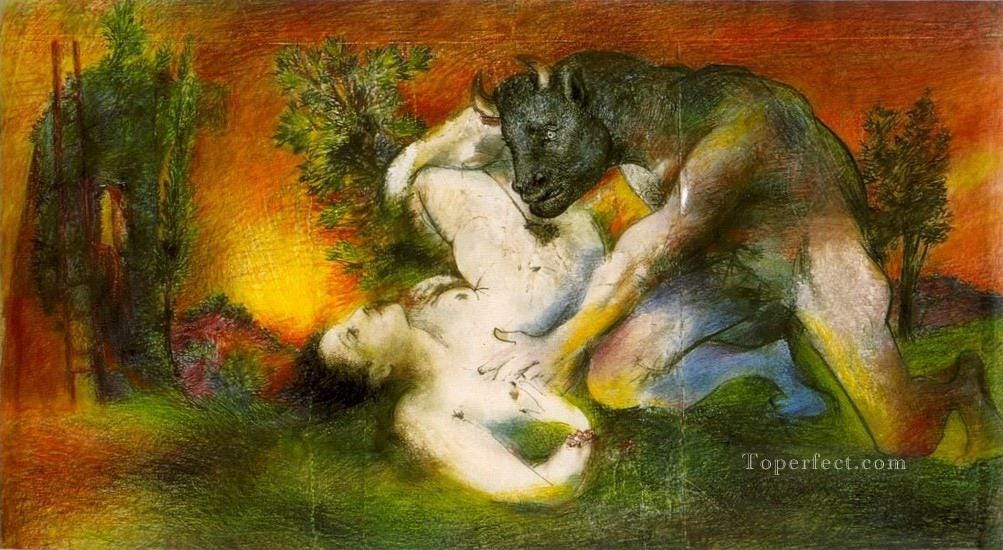

Fast-forward to Picasso’s Minotaur and Woman.

If you ever want to watch someone squirm in an art museum, show them this painting.

Half-man, half-bull, fully erect—mythically and metaphorically—the Minotaur looms over a nude woman in a pose that’s equal parts sensual and unsettling. Is it desire? Domination? A dream? A threat? The image won’t let you settle into one answer. That’s part of its charge.

Some see mythology. Others see violence. Some whisper “pornography” and look away. It’s not just how we look—it’s what shame has taught us to see.

We now live in a culture where nudity in art must defend itself. The sacred nudity of ancient times has become the oxymoron of modern life. We’ve inherited a discomfort that wasn’t always there—and drag it into dressing rooms, relationships, and intimacy.

We’re not just censoring what we see. We’re censoring how we feel.

Censorship isn’t just something that happens to art. It happens to us.

We don’t just blur bodies—we blur the permission to enjoy them.

We second-guess attraction.

We hesitate in pleasure.

We edit our impulses mid-sensation.

This isn’t just a cultural hangover. It’s a private echo chamber. One that gets especially loud when we start to feel good. Because here’s the next layer of shame—one that doesn’t get talked about enough: the shame of receiving pleasure.

Not just expressing desire—but letting it in.

Letting it happen.

Staying with it.

For many—especially those raised in conservative, religious, or sexually repressed households, pleasure itself can feel like a betrayal. A sign of weakness. A moral failure. We were taught to feel guilty not just for what we want—but for what we enjoy.

That guilt doesn’t vanish with age. It follows us. It walks into the bedroom with us. It lies beside us in the dark. It’s there when we hesitate to undress. When we apologize for wanting. When we don’t ask for more—even when we ache for it.

Eventually, we stop needing anyone to silence us.

We do it ourselves.

We ration joy.

We dilute intimacy.

We trade honest sensation for curated performance.

So we grow up and discover not just shame in wanting—but shame in accepting. Not just shame in being seen—but shame in being touched, in being held, in being moved. The shame of letting something good actually reach us.

That’s what censorship does. It doesn’t just restrict images. It builds emotional firewalls between the viewer and the viewed. Between the body and the experience of living in it. Between the eye and the permission to feel.

We forget that nudity was once a form of reverence. That pleasure was once sacred. That desire was once seen as a sign—not of sin—but of life.

This isn’t just about censorship in the gallery. It’s about what we bring to bed. What we carry into relationships. What we pass on to the next generation when we don’t question where the shame came from.

When did the human body become NSFW?

Installment C: The Body as Compass: Erotic Maps Across Cultures